Three days after Hurricane Helene blew through Western North Carolina, smashing trees and washing whole neighborhoods away like Autumn leaves, my sister Brita and her family left their home in Weaverville—a village directly north of Asheville—to shelter with family here in Durham. Their own house survived, thankfully, but they were without power and water. Their children’s school was indefinitely closed, as was the clinic where Brita was doing field work for her Occupational Therapy degree. With highway 40 blocked, what’s normally a three and a half hour drive east took them nearly eight hours as they wound their way down into South Carolina on the only open road and then back up, northeast. They’ve made a couple of trips back to the mountains since then (I-40 has reopened) to gather more of their things and to deliver trailersfull of needed supplies to relief organizations and to check on neighbors, but will likely be here for at least a few more weeks so my sister can continue her fieldwork (she was reassigned to a clinic in this area) and her girls can attend school.

One of the things I immediately felt when Helene first hit Western NC, and which I’ve heard from a number of people since, is confusion that this place hailed as a “climate sanctuary” or “climate safe” location is clearly not, in fact, safe from the climate crisis. Of course, if we’ve been paying attention, we know that nowhere is actually safe—the planet is not compartmentalizable—but it can be tempting comforting for those of us in the global north to tell ourselves that we’re protected, or at least that there’s somewhere we could go, in a pinch, that would be. That veil is quickly being removed and tossed, wildly, in the hurricane-force winds.

I haven’t been to Western NC since the storm—strangely, I was there just one week before it happened to participate in the Punch Bucket Literary festival—so I’ve been reckoning with the devastation there through supporting those closest to me. My sister’s family, yes, but also my husband who traveled with my brother-in-law and niece for one of the supplies-delivery trips and was shaken by the enormous and sudden changes to the landscape, and also my dear friend, the climate photographer and journalist Justin Cook, who has been traveling there to document the destruction and impact on lower-income residents of Swannanoa, NC. I understand through these loved ones that being there, on the ground, is heavy.

I believe we should all be using our talents and other resources in whatever way we can to reduce both current and future climate harm, while also taking care of our own nervous systems as much as possible, since a regulated nervous system can be a huge gift to those in distress and those most impacted by climate disaster and injustice. For the past two weeks, in addition to supporting relief efforts financially and making phone calls on behalf of my sister’s family (to help find them temporary housing and schooling, etc.), I realized that the best gift I could give those in distress around me was to stay as grounded and regulated as possible. For me, that meant limiting my consumption of news and digital media, taking up an embroidery project to have at hand in the evenings, and baking bread and granola for overwhelmed loved ones who might need a snack. It meant being available to family and friends who needed to share about what they’d seen, to express their grief and rage.

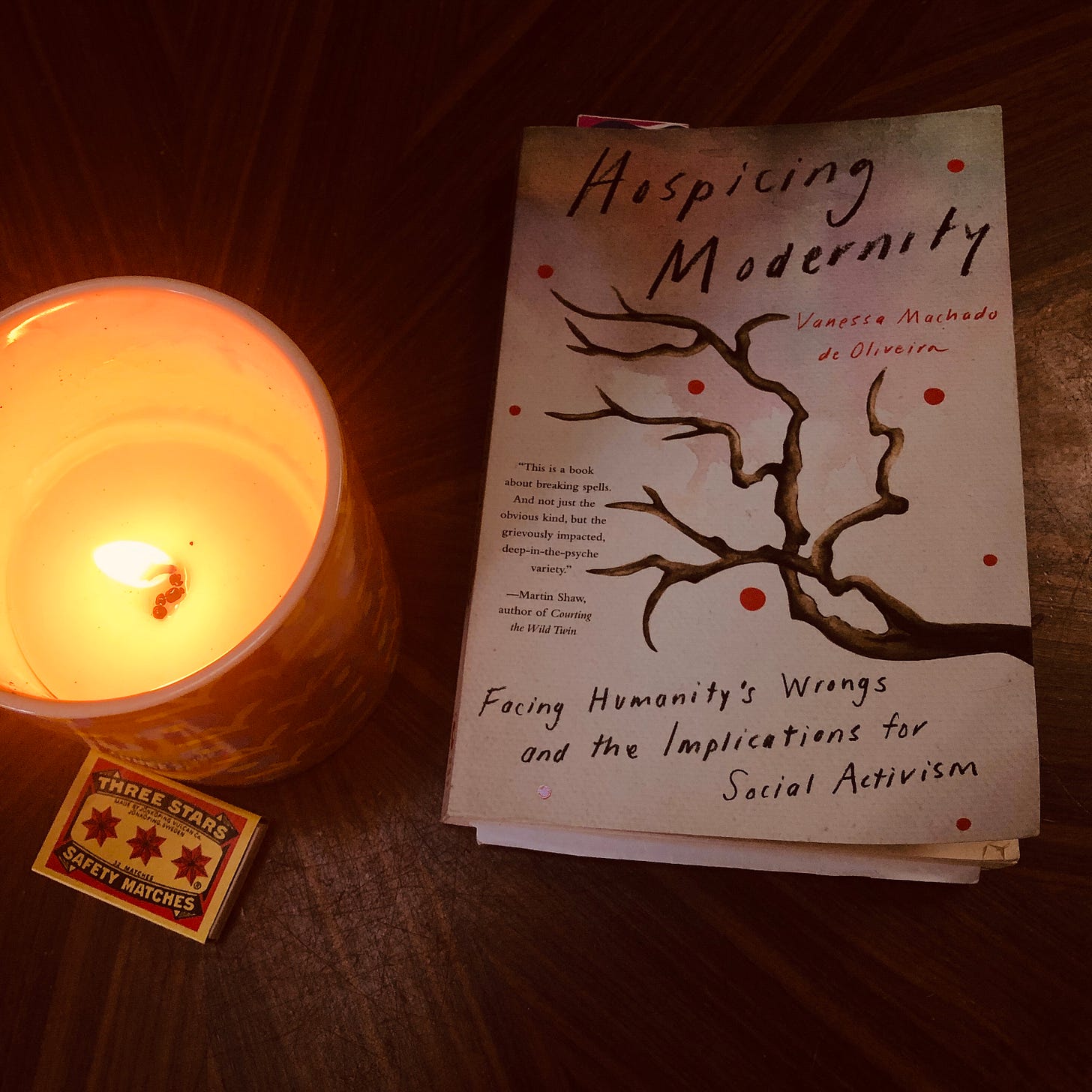

Krista, my other sister and partner at The School for Living Futures, and I have been talking a lot recently about our purpose with SfLF and what it means to be working for culture change when the future is so uncertain. In our biweekly gatherings to discuss the book Hospicing Modernity this fall, our group has been reckoning with Vanessa Andreotti’s observation about how our imaginations are limited by modernity so that it’s nearly impossible for us to imagine what life would look like outside of its thrall. What future can we work toward when we can’t see the future? How can we reconcile the sense of urgency we feel in finding solutions to the climate crisis, when both urgency and the idea of fix-all solutions to complex issues are manufactured by modernity itself, the same system that created the climate crisis?

There are not, in fact, easy or single answers to these questions, but reading Hospicing Modernity has been helping us explore the questions more deeply. As a writer, I believe one of the gifts we artists can offer is our ability to bring our full senses to the present and remain open to possibility and uncertainty. As a curator and community-builder, I believe part of our work in this time of atomization, polarization, and fear is to practice radical hospitality: to welcome each other, break bread with each other, form and strengthen connection both within and beyond our habitual clans.

articulates this well when he talks about “regrowing a living culture,” an effort he explains in his most recent Substack post, which I’ll quote at length because it so perfectly addresses what Krista and I have been holding:A living culture is a way of being human together that needs its members to come alive, to show up and turn their lives into a gift, a culture that can’t afford the waste of people not coming alive. There’s a kind of high-flown talk I sometimes hear about the “evolution of consciousness”, where the assumption seems to be that it’s the conditions of modernity and technological progress that make it possible for people to come “fully alive”, but it seems to me almost the opposite: that it is only under these conditions that a society can afford the amount of lostness, trappedness, unfaced fear and unfulfilled potential that comes of not attending to the ways in which we come alive as the creatures we are, with the particular gifts we came with or that the passage of life has brought us.

As Vanessa Andreotti once said to me, from an Indigenous perspective, the way of life of modernity looks a lot like “everyone sitting in kindergarten class for their whole lives, singing the ABC song over and over.” The answer isn’t to fetishise Indigeneity, or to sink into mourning over some imagined pristine Other way of being human, but to start from here, looking for the traces, the places where we do come alive, the role that we play for each other in this process.

So this is where we are this season: holding the inescapability of rupture and loss and the pressing need for those of us who can help reduce the harm alongside the deep, slow work of growing up, starting from where we are here at the end of the world as we know it, gathering with friends new and old around a fire to tell our stories and begin tickling our imaginations about what new stories we might live into existence.

I’ll leave you with a poem from Adrienne Rich, published in her 1951 collection A Change of World. Although much in this poem still rings true, I’ll point out that we can no longer effectively (or ethically) “close the shutters” against the rising winds.

Storm Warnings

The glass has been falling all the afternoon,

And knowing better than the instrument

What winds are walking overhead, what zone

Of grey unrest is moving across the land,

I leave the book upon a pillowed chair

And walk from window to closed window, watching

Boughs strain against the sky

And think again, as often when the air

Moves inward toward a silent core of waiting,

How with a single purpose time has traveled

By secret currents of the undiscerned

Into this polar realm. Weather abroad

And weather in the heart alike come on

Regardless of prediction.

Between foreseeing and averting change

Lies all the mastery of elements

Which clocks and weatherglasses cannot alter.

Time in the hand is not control of time,

Nor shattered fragments of an instrument

A proof against the wind; the wind will rise,

We can only close the shutters.

I draw the curtains as the sky goes black

And set a match to candles sheathed in glass

Against the keyhole draught, the insistent whine

Of weather through the unsealed aperture.

This is our sole defense against the season;

These are the things we have learned to do

Who live in troubled regions.Upcoming Event

If you’re in the Triangle region of North Carolina, you’re invited to a joint reading and performance by me and my dear friend, the amazing writer and interdisciplinary artist Sarah Minor tomorrow, October 17, at 7pm at the Birdland Gallery in Raleigh.

I will be reading from Feathers: A Bird-Hat Wearer’s Journal, and Sarah will be reading from her most recent book, Slim Confessions: The Universe as a Spider or Spit. There will be feathers, there will be slime, there will be featherslime (or “bird goo” as we like to call it), there will be wine and snacks, there will be performance from two strange books. We will wear fabulous earrings. We want to see you there.

"Radical hospitality," a great way to kick off my morning. Thanks, Sarah Rose. I think our "sense of urgency" is real; how could it not be. But, I think it is also a trap as you imply. Andreotti is encouraging patience as we witness the decline of modernity. In this place of patience hopefully we can begin to envision what "the regrowth of a living culture" really looks like. Possibilities will emerge during this transformative period. Societal structures will begin to materialize. As bad as the crises are that we have faced and as bad as the crises yet to come, they are also sarcophagi stones already in use as we build modernity's final resting place.

Greeting Sarah Rose, I'm in Black Mountain which is the town east of Swannanoa. In between working in the trenches, I've been hauling around What If We Get It Right by Ayana Elizabeth Johnson. She's also here on Substack. If you haven't read her, I think you would appreciate her 20 interviews with epic climate/environmental people. in kinship, Katharine