Texture and Nature

An interview with Future of Water artist Patrizia Ferreira

“Once I discovered I could imitate nature through texture, I was besotted,” confesses textile artist Patrizia Ferreira, one of the artists contributing work to the upcoming Future of Water art show commissioned by The School for Living Futures. And it’s that sense of besottedness – with texture, with materials, with creation, with water and weeds and stones – that attracted us to her work and left us similarly in love.

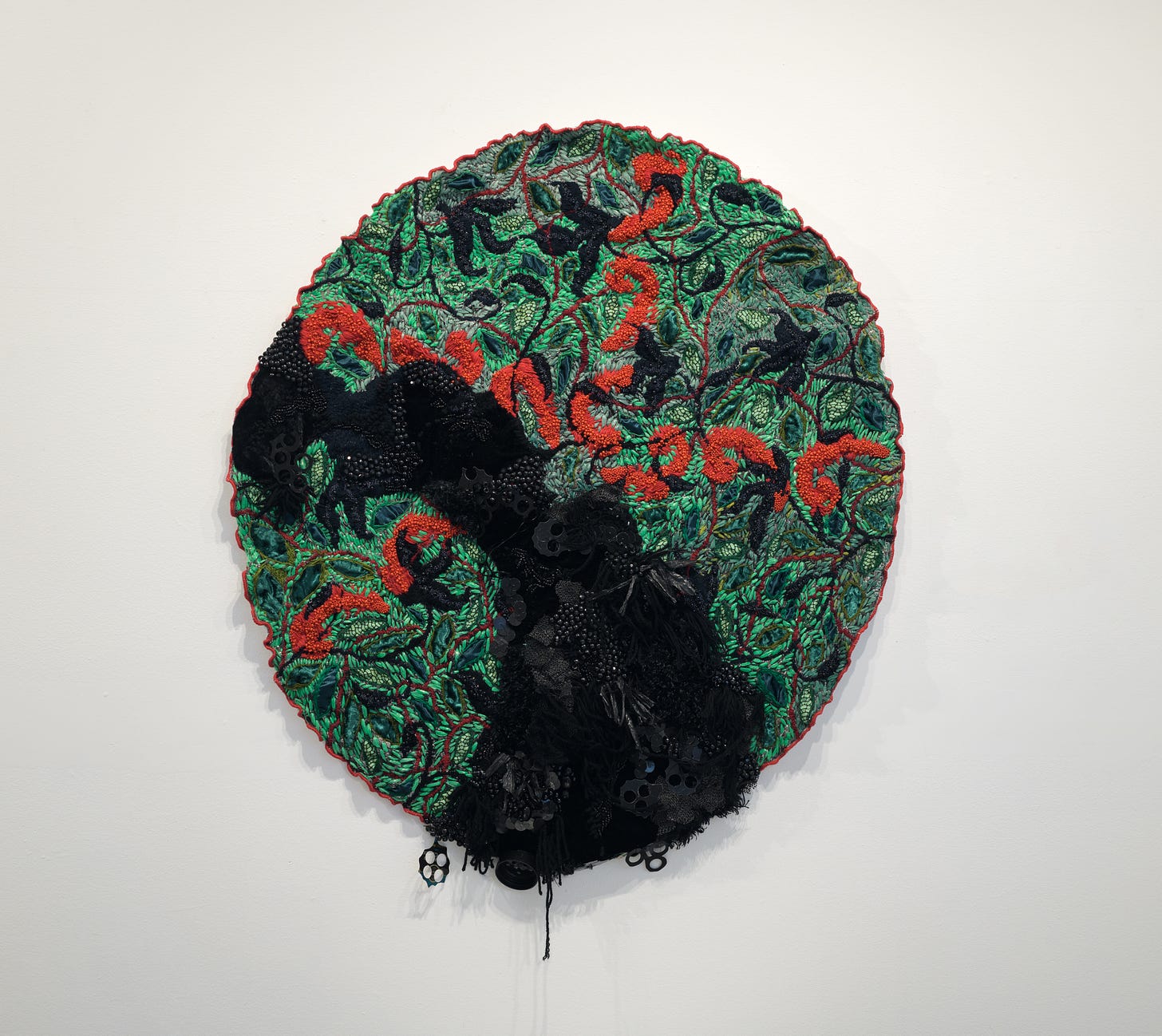

In Ferreira’s pieces, many of which seem to exist at the juncture between tapestry and sculpture, I also feel the past and future meeting: The generations of women through history and many cultures who’ve spent countless hours working threaded needles through fabric, the stories that live deep in our bones (the Garden of Eden, the Tree of Life), but also the potential tendrilling out from these stories through our present and into the unknown (ropes as roots splaying across the gallery floor toward the viewer, the dark chasm splitting the garden).

I hope you’ll read on to learn about Patrizia’s childhood in Uruguay, her inherited love of fabric and textile, her relationship with water, and her deep desire to “sensitize” people with her work. If you live in the Triangle region of North Carolina or find yourself this way in May, I hope you’ll also take the opportunity to see some of her gorgeous work in person at the Future of Water show.

SRN: Patrizia, I would love to start this conversation by learning a little more about you and your background as a textile artist. When in your life did you begin working with textiles, and how did it come about? Were there textile arts around you or artists in your family? What draws you to textile and fiber art as a medium?

PF: I grew up surrounded by women who valued, and appreciated textiles. There were tablecloths and napkins reserved for special occasions. Passed on from previous generations, mended and hand-washed with care. Clothes were also items of reverence. My Italian grandma would travel back home and bring back dresses from my Italian cousins. Beautiful handmade dresses, made of the most covetable fabrics, velvet, silk taffeta, lace, linen. I would drool over them. I believe this early connection to the material has forever left a mark, imbuing my current work with deep connections with my own personal history and a different time.

Although I have a very encouraging mother who always stimulated me to be creative, signed me up for art classes, had inspiring art and architecture books laying around the house, I didn’t initially consider a career in textiles or any creative career. I grew up at a time in Uruguay where the career options were limited. The country had recently come out of a dictatorship. The economy was slowly being rebuilt. Also, my mom is an architect, my dad a civil engineer and everyone in my family is a professional in a traditional career. I was encouraged to pursue a pragmatic career instead. So while I would have wished to study fine arts, I instead enrolled in dentistry. I attended for a whole year and had it not been for a long strike that came about at the end of it, I may have taken longer to consider other options. However, during the long break a quiet voice inside of me told me I should try something else. The School of Design had just opened in Uruguay and I decided to apply. I was admitted and in the second year the option of doing a concentration in textiles came up and I went for it. The rest is history. I found my path. It wasn’t fine arts, but I fell in love with all the different facets this new path could bring, I considered being a fashion illustrator, a fashion designer, a fabric designer, a knit designer. So many creative options! I ended up settling for print design because of my love for patterns, drawing and painting.

“Once I discovered I could imitate nature through texture, I was besotted.”

Textiles are fascinating. Their versatility is limitless. The fact that they can be rendered bi or tridimensional, flat or textured, glossy or matt, furry or laced, is for the artist in me an open door to infinite creations. Once I discovered I could imitate nature through texture, I was besotted. That didn’t happen right away. I had to get a bachelor in textile design, then work in the industry, then pursue a graduate degree in the USA. Start working in my field of expertise, sit at the computer for hours, to slowly on my own time as a need to release my deep need to use my hands in a creative manner begin to discover the utter joy of making. All the techniques I employ today, I taught myself. It started with design, but it has slowly moved back to the beginning, to my first love, fine arts.

SRN: I’m interested in your comment about imitating nature through texture. Could you say a little more about that, and perhaps – since you’re part of the Future of Water exhibition – your relationship with water and how that shows up in your work?

PF: Nature moves me. It touches me deeply. Having grown up in Uruguay, with water all around me - Montevideo, the capital, is by the Rio de la Plata, the widest river in the world that connects at its widest mouth into the Atlantic ocean - I have always felt a profound connection with this element. The shore and the life that grows at its threshold fascinates me the most. Texture and pattern is how I connect with it. I have this innate compulsion to want to preserve it in some way. Recreating these moments of awe is a way of prolonging this feeling, preserving it for posterity. The other big variable in my work is the idea that everything is connected. Nothing happens in isolation. The Pacific Garbage Patch, “far away” in the Pacific, is not an isolated, remote event. It is the confluence of garbage coming from myriad waterways that lead to this particular place. Drawing attention to the many ways in which we can experience beauty, and be more respectful of our surroundings, is one of the biggest reasons why I create.

Severe drought in the southern hemisphere, Uruguay became the first capital in the world to hit day zero in June 2023, when it ran completely out of water, is also not an isolated event. Uruguay is experiencing drastic changes in its weather patterns, losing its four seasons and experiencing extreme weather events of droughts, extreme heat and flash floods which are historically unprecedented. This is the result of climate change. Climate change is affecting us all and putting everything in perspective. Water, like blood in our bodies, is connected through the many rivers and waterways to the oceans. Our planet is roughly 70% water. Human life cannot exist without it.

SRN: Do you still have family in Uruguay, and how often do you visit there these days? What is the state of the climate movement and conversation about the changing climate there?

PF: Yes, all my family is in Uruguay. We visit every year for about a month. For my kids who grew up in the US and have moved across states several times throughout their life, Uruguay is for sure their second home. A place that is always there, year after year. For me it still is Home. The one and only.

Uruguay is investing really hard in renewable energy, recycling, eco farming and reducing our carbon footprint in every which way, but being such a small country and tiny economy there is only so much we can do. The climate movement in Uruguay is not a choice but rather a survival imperative. Currently, environmental engineering is one of the most popular degrees for young men and women, as well as degrees in information technology, eco architecture, and sustainable farming which will hopefully allow Uruguay to improve their outcomes as climate change continues to create havoc across the world but particularly in the global South.

“My goal is much more humble. I simply hope to move people, to sensitize people, as they experience and encounter the work.”

SRN: I’d like to know more about how you think about your role as an artist in light of the climate and other environmental crises. Do you think of your art as a type of activism, or is it something else? Do you think about the audience for your work while you’re in the process of creation – about what they might understand and experience from it – or does that come later?

PF: Thank you for that question Sarah Rose. It’s always a goal when creating the idea that it may reach people and trigger positive change. While I love that idea, my work is truly personal. My goal is much more humble. I simply hope to move people, to sensitize people, as they experience and encounter the work. The work I create is a subjective response to my environment and to my own personal experiences. I feel my work as an extension of myself. My visual language is in great part instrumented by my past, growing up in Uruguay at a time where our economy was suffering, and the choices of products available were very few and far between. I often think it is this past that I try to recreate. Perhaps in that way it is a form of resistance, in that I resist what modern society sells me as the ideal model. A model that wants me to consume all the time. I like the idea of making something out of nothing. The idea that a tiny action when accumulated becomes a colossal event. Nature operates in this way. The themes that constantly play in my head have less to do with the current climate situation and more to do with universal truths told by our ancestors. In my work I try to recapture this essence, and return to the past in an effort to remember.

“The Future of Water: a speculative art show” will open at Durham Art Guild’s Golden Belt Gallery in Durham, NC, on May 11 and run through May 28. This show will feature new work by Lucas Brown, James Keul, and Patrizia Ferreira. You can RSVP for the opening reception here.