Ancestral Legacies

An interview with Future of Water artist Lucas Brown

I first encountered the work of artist Lucas Brown without knowing it. Down Yonder Farm in Hillsborough, North Carolina, a property owned (and reverently tended) by my friend, Jessie Gladdek who inherited it from her own parents, contains the historic Ray Family cemetery, a burial site for Indigenous, African, and Melungeon ancestors from prehistoric times to 1928. Lucas Brown, at the invitation of Beverly Scarlett, Director of Indigenous Memories, was the artist who painted the large mural erected there to recognize this sacred site. I’ve looked at this mural many times on my wanderings around the farm, never knowing, until recently, who painted, so carefully, the faces of the ancestors lining its border, or painstakingly wrote out the known history of the site, beginning in the 1200s before European contact.

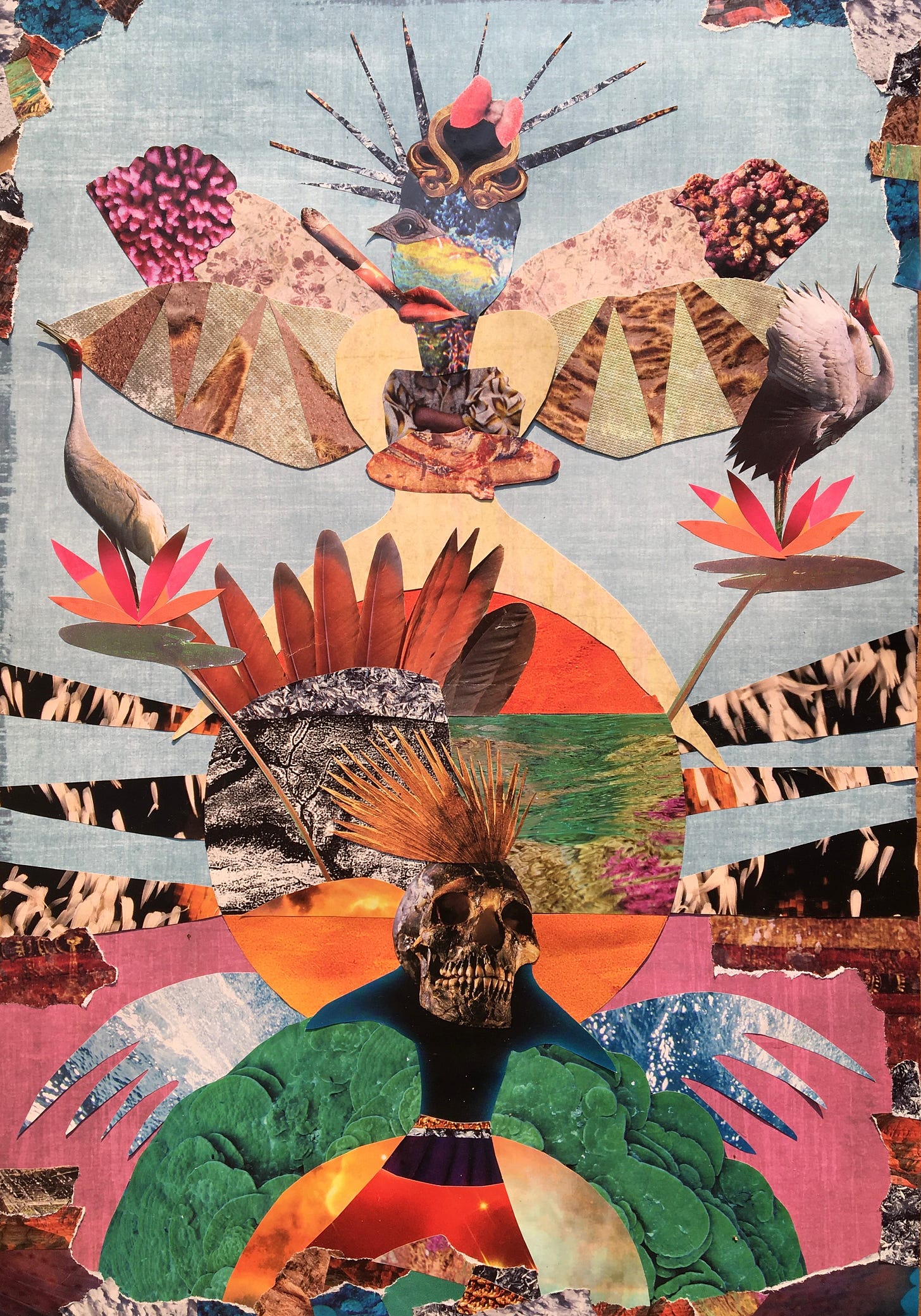

I recognized the image of the mural immediately when I came across Brown’s application for the Future of Water exhibition School for Living Futures has commissioned in partnership with the Durham Art Guild, and we were deeply impressed by the ways in which all of his work breathes with the complex histories, lineages, and weavings of harm, resilience, and repair that surround all of us, as well as how his work lives and moves in community.

Read on for my discussion with Lucas Brown about identity, play, healing, and the children’s power to jolt us into new relationship with reality.

SRN: Lucas, I was so moved by the “About” statement on your website, which is not my usual response to online biographies! In it, you write,

I come from generations of extended mixed British/Scottish/Other ancestries, kin to beautiful beings, kin to those who caused great occupier harm, kin to those that built the enslaving antebellum homes and those that enlisted in manifest destiny violations, kin of tenet and tobacco farmers and mill workers searching for and taking-of-place in a colonizing south, kin to forgotten musicians and mountain top singers, dancers, poets, queer laughter-a-teers, and all those that remember how to honor the spirit of land, water and interdependence.

I think the reason this statement is so moving to me is the way you’re able to dance with the complexity of identity here, simultaneously acknowledging lineages of beauty, care, and great harm without any of them being diminished. Can you tell us more about the process you’ve gone through (and are in) with these intertwined heritages, and how they show up in your life as an artist?

LB: Such a beautiful question, thank you. I’m grateful for the plethora of folk that have walked the path of identity reclamation and who continue to walk it boldly. The many-other helps me stay courageous and persistent in breathing love into the fear that can shape my psyche and habits. One of the many devastating effects of colonial white supremacy is the continual erasure of ancestral stories, how it shapes bodies' understanding and expression of oneself, feeds anger, resentment and inherently shuts down healthier intimacy and gifts one may bring to the world.

My art journey re-began as a latent process of unpacking ancestral legacies through art, which has included processes of listening and validation of that which has been invalidated and generally violated for many centuries through the brutality of Patriarchal hijacking of Christianity. In fact, some of my first lino-cut pieces originated from spending time with a book on torture devices of the Inquisition, opening up my senses and beginning to feel the images as the real people and events they were depicting, to actually validate their tremendous pain and the horrific violence that the state and religious institutions were inflicting upon the people.

I have Huguenot ancestors that fled regions of France, became British and then extended that trauma either through coercion with the state and empire building/settling and/or direct violence. With art, ritual, and art-as-ritual I began tracing towards the present. For much of this time, sitting, listening, and honoring all the ways beings show up in me continues to inform an immensity of self and different responsibilities therein that shape my orientation of self today. There are many people to thank that have supported this journey, and I’d like to give special attention to the late Indigenous poet and activist John Trudell for the DNA Ancestor album he recorded and how it shaped my understanding.

SRN: Can you say a little more about your art life – both its beginning and its “re-beginning”? When did you first come to painting, what has your art education been like, and what are your hopes for where it will take you?

LB: Thank you for the question. I’d like to pause and acknowledge that this morning the continued bombardment of the Rafah refugee camp by Israeli and American violence is ongoing, that over 12,000 children will not wake to offer their gifts to the world because they’ve been brutally killed.

My art life extends into my work as a preschool teacher as I want to believe that supporting early exposure to healthy connection, identity formation/expansion/play, boundaries and love of self/other and historical truth will continue to bring forth a world where this form of violence ceases to occur, and that cultural and earth-given creative gifts can flourish. My creativity was present as a child, and I only recall one freehand drawing of a leopard and forest, and how proud I was of it. I think it was from a puzzle box that I loved and stared at all the time. However, I also experienced chronic emotional, verbal and physical abuse within my family that began to take its toll on a healthy unfurling of those gifts, while most of my energy also went into sports as my physical privileges were prioritized.

Through my twenties and into my thirties, while working mostly as an educator, I tried to carve paths with music, writing and theater that generally ended in self-sabotage and frustration, which is where the cyclical, habit-forming trauma was playing itself out. At 33, I was working as a TA in a kindergarten class. One day I was hanging with them during the art block, working on my own drawing, when a sweet kid came over and stood next to me and said “Wow Mr. Brown, that’s beautiful, you’re an artist” and I immediately began tearing up, and that nudged me along into what has been a long healing journey, as those were words I needed to hear and he spoke right to my soul with that acknowledgement.

Presently, I paint because it feels good, it connects me to self, to play, to my love and to the simplicity of creating something. There is a sensuality to it that is just delightful and always kind of of turns me on where it becomes pure pleasure. It’s that excitable moment when colors blend in a way and the texture is just right and somewhere inside a big yes erupts. With regards to social responsibility, I love that it continues to connect me with others, their stories, to be in service of just transitions of land to Black and Indigenous peoples, support a consciousness of care, witnessing and acknowledging the beauty of others. The education comes from simply participating with others, hearing their stories, learning some approach or technique, and being grateful to experience insight into their longings and imaginings. I’m still toying with some focused MFA possibilities at some point–we’ll see.

SRN: Thank you for that acknowledgement, Lucas, of the ongoing genocide in Gaza. I was glad to see that our city of Durham, NC, passed a ceasefire resolution yesterday as of this writing (February 20), becoming one of only 70 cities across the nation to do so. We need to keep the pressure up on the national level to get this madness to stop.

That’s a beautiful story about the child affirming your talents and heart-longing as an artist. It’s so beautiful when we can do that for each other, and children can be particularly good at seeing what’s present. In my own parenting of my neurodivergent child, I’ve been learning about and using a behavioral therapy technique called the Nurtured Heart Approach, where the focus is on healing our children and ourselves through regular recognition of their greatness, and bringing intensity and connection to all the things that go right. I’ve found it to be a wonderful reframe and reminder of the ways we can be with each other, not just children, to just recognize each other for the beauties that we are and can be when so many of us are working with old, deep layers of shame, trauma, and repression.

Finally, I’m wondering if you could say a little more about how you see the role of art in the climate crisis and in the intersecting injustices of environmental, racial, gender, and economic oppression? From what you’ve already shared, I’ve gathered that, for you, one of the greatest powers of an art practice is its ability to heal/change ourselves, as well as its power as a connector between people. Would you like to expand on that or add to it?

LB: Mmmm, thanku Sarah. Feeling the fulling moon, the shift of rain to star-lit evening, the connection you are deepening and sustaining with your own child through the nurtured heart, after a beautiful creative afternoon with a handful of kids in the rain at preschool today. We are intertwined with a tremendous amount of connection to many beings, on many planes of perception, and wired with many modalities of very tender sensitivity, informing us of the many beings that have been here before us, sustaining/creating our lives. Art, as truth-bearing co-witnessing, enhances our listening, trusting, our co-created connection, and our humility to all that we are responsible and accountable to. Bless all that unfurls regarding justice and accountability to one another as we heal our perception and participation in connection.

“The Future of Water: a speculative art show” will open at Durham Art Guild’s Golden Belt Gallery in Durham, NC, on May 11 and run through May 28. This show will feature new work by Lucas Brown, James Keul, and Patrizia Ferreira.

"that over 12,000 children will not wake to offer their gifts to the world because they’ve been brutally killed."

Life sometimes feels surreal when I can look through my screen and read what i want, see what I want, and write what i want, when others will never see the light of day again. This statement is powerful and really puts life into perspective. Thank you so much for this wonderful article.