Happy new year, and hello to the new subscribers who’ve found me in recent weeks. I’m so happy to have you along with me at the start of my second year of writing Wilderment. This space—which continues to evolve—is where I share some of my explorations at the intersections of poetry, literature, and the living world (nature), as well as questions and practices for “living well” in this time. If you enjoy this work and are willing and able to support it, please consider becoming a paid subscriber this year. I will share more soon about the big project I’ll be undertaking in 2025, and your contributions are, in part, what enables me to dedicate myself to writing and community projects.

Last weekend, Brandon and I took Oliver and a friend to a planetarium for the first time. I had memories of going to the same one—the Morehead Planetarium on the campus of the University of North Carolina—for field trips as a child, and had been looking for an opportunity to experience the magic of the starry dome with him. The show we saw was based on the Magic Treehouse books, of which we’ve read many, and follows the book characters Jack and Annie as they answer a series of questions about space that many children likely share (How long would it take to fly to the sun? What is it like to travel in space? How many stars are in the sky? Why is the earth so special?).

Oliver was sufficiently amazed by the experience of the constellated dome, and clung to me for comfort in moments as we seemed to leave earth and move through the expanse of space. Together as a family—my right arm wrapped around Oliver’s small body, my left hand in Brandon’s hand—it felt good “both going and coming back,” as Robert Frost says in his poem “Birches.”

After the Magic Treehouse program, the live portion of the show offered a tour of the night sky here in the piedmont of North Carolina on that particular night. We saw the moon (a waxing crescent), Venus and Saturn in their bright positions slightly below the moon, Mars and Jupiter further to the south, and the constellations Andromeda, Cassiopeia, Orion, and Canis Major and Minor. The children were encouraged to learn the “official constellations” that astronomers use, but also to employ their imaginations to identify their own (“a mole!” shouted a child near us, “an eagle’s head!” “A hotdog!”).

The part of the show that struck me most vividly, and which I also remember from my youth, is the moment in the presentation where the planetarium guide “turns off” the light pollution from our metro area so that we can see all of the stars that would be visible to the eye without artificial lights. The difference is astounding—like taking a blindfold off, or the moment when one of those “magic eye” images (remember those?) finally comes into relief and your view takes on depth, form, meaning.

I wrote about the significance of light in my Solstice post last month—the sacred practice of protecting our small lights in the darkness of this season—but of course this light would be meaningless without the darkness in the first place. In truth, we live in a light-obsessed culture, a culture in which we’re expected to stare constantly into blue-lit screens in perpetually illuminated cities where we can’t even see the stars. A culture fixated on the light of facts (real or alternative), on “information,” on “the news,”1 the all-seeing scroll. It seems we are less comfortable with darkness—literal darkness, but also its associations of unknowing, of confusion, of depth, of intimacy.

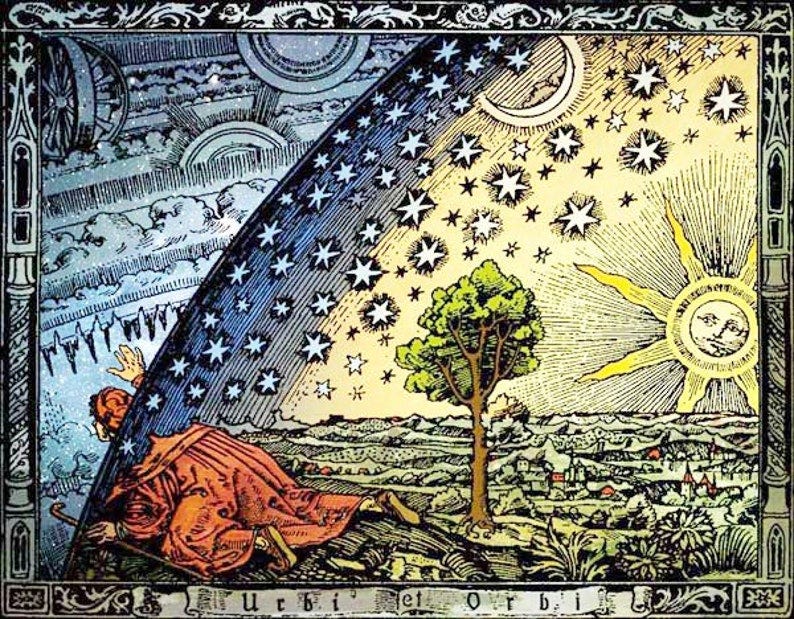

In our drive to know, to see, many of us (including myself) have actually become dis-oriented in the real landscape, in our places on earth. Many of us couldn’t pick out north from south in a given room, let alone identify the constellations in the sky or describe the boundaries of their watershed. As Joshua Michael Schrei points out on a recent episode of The Emerald Podcast, many people in urban areas might go through their whole life without ever seeing the band of the milky way, the wondrous view of our own galaxy that has inspired stories for thousands of years in cultures all over the planet. The milky way that is the milk from the goddess Hera’s breast, that is Freya’s necklace, the blood from the severed tail of the dragon Tiamat, the Goddess Nut, the River Ganga in the Sky, and a trail of corn where a dog dropped if from his mouth while running away.

And so, lately, I have not only been cherishing the light, but also pining for the dark, a night pure and thick as a womb without the rough speculum of electric light. I want to feel the feral black closing in on my house’s walls, its hair shining and slick as God’s cloak. And to be clear, when I say dark, I don’t mean evil, though there may rightly be a touch of fear. Yes, a bit of that primal kind that tingles your skin so you can smell your own sweat, that calls you in to the flickering warmth of the hearth.

I light a candle at my bedside each night and each dark morning, and watch the fingertip of flame pointing ever up. The edge where form blurs into space, light into dark. It is a holy meeting there, a ticklish disappearing, the seen into the unseen.

To close, here are some questions I’m holding, in case any of them inspire or resonate with you as well:

How can I honor literal darkness in this season?

What does darkness have to teach?

What are practices of dark and light that I can incorporate into my life, dark/light hygiene?

And here are some things I’m doing:

Lighting a beeswax candle at my bedside for a while every evening before bed, and every morning as I wake slowly, with no other lights in the room.

Noticing what I can in the night sky, despite the light pollution—picking out the planets and constellations I recognize, and tracking the cycle of the moon.

Journaling/writing about the aspects of darkness.

Planning a camping trip to an International Dark Sky Park only a couple of hours away from me.

I’m also reading poems that bring forward the beauty and power of darkness, including these two.

Coal by Audre Lorde I Is the total black, being spoken From the earth's inside. There are many kinds of open. How a diamond comes into a knot of flame How a sound comes into a word, coloured By who pays what for speaking. Some words are open Like a diamond on glass windows Singing out within the crash of passing sun Then there are words like stapled wagers In a perforated book—buy and sign and tear apart— And come whatever wills all chances The stub remains An ill-pulled tooth with a ragged edge. Some words live in my throat Breeding like adders. Others know sun Seeking like gypsies over my tongue To explode through my lips Like young sparrows bursting from shell. Some words Bedevil me. Love is a word another kind of open— As a diamond comes into a knot of flame I am black because I come from the earth's inside Take my word for jewel in your open light. Darkness Starts by Christian Wiman A shadow in the shape of a house slides out of a house and loses its shape on the lawn. Trees seek each other as the wind within them dies. Darkness starts inside of things but keeps on going when the things are gone. Barefoot careless in the farthest parts of the yard children become their cries.

Yours in darkness and light.

SRN

I use quotation marks here to indicate the fact that, as Neil Postman points out in his classic and prescient book, Amusing Ourselves to Death, that “the daily news” is a made-up concept that came about with the invention of the telegraph.

Oh, I so love the Morehead Planetarium, even though I'm now clear across the continent from it. Thanks for this lovely remembrance.