Women and Wilderness (2)

Identity, wildness, and the domestic in Sarah Piatt and Sylvia Plath

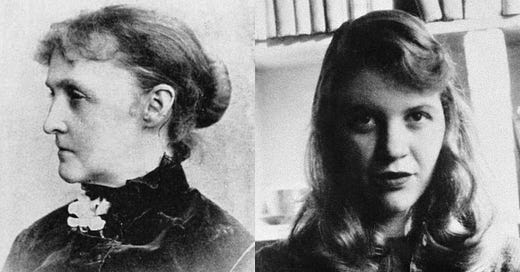

This post continues my exploration of women and wilderness in American women’s poetry that began here. In this installment, I look at wildness and domesticity in the poetry of Sarah Piatt (1836-1919) and Sylvia Plath (1932-1963).

Have any of you heard of the poet Sarah Morgan Bryan Piatt? If the answer is no, you’re not alone. Sarah Piatt (1836-1919) was a highly accomplished American poet who was widely published during her life but who, until recently, had been forgotten/lost to readers and scholars alike. She’s one of the women poets who has benefitted from recovery projects such as the ones undertaken by Second Wave feminists in the latter decades of the 20th century, though Piatt’s recovery was more recent.

Piatt grew up in a blueblood family on a plantation outside Lexington, Kentucky, and several of her poems interrogate the institution of slavery and her personal implication in that institution. The persona she assumes in her poetry is not the conventional naïf or simple and virtuous wife and mother, but a sexually mature woman with her own history, her own desires, her own thoughts: In short, a fully-formed person.

Likewise, Piatt’s poems often imbue domestic landscapes with a complicated and unsettling atmosphere, steeped in American sins. For example, “A Child’s Party,” a narrative poem about a childhood memory at her grandmother’s home, reveals how every element of the domestic sphere under the institution of slavery—from the fine china, lace, and carpets to the children’s games—is infected with racism such that no one and nothing is innocent. The poem “The Funeral of a Doll”* contains a similarly eerie domestic atmosphere in its description of a funeral for the “waxen saint” of a girl, “Little Nell,” about whom the reader can never quite discern whether she is a doll-like girl, or an actual doll. In the process, however, the speaker emphasizes the smallness, daintiness, and femininity of the occasion so consistently (“She, too, was slight and still and mild”; “Her funeral it was small and sad”; “And there is no one left to wear/ her pretty clothes”) that the poem becomes saturated with irony and unease. By emphasizing the cuteness of the funeral rather than its grief, Piatt points at the trivialized lives of women and girls.

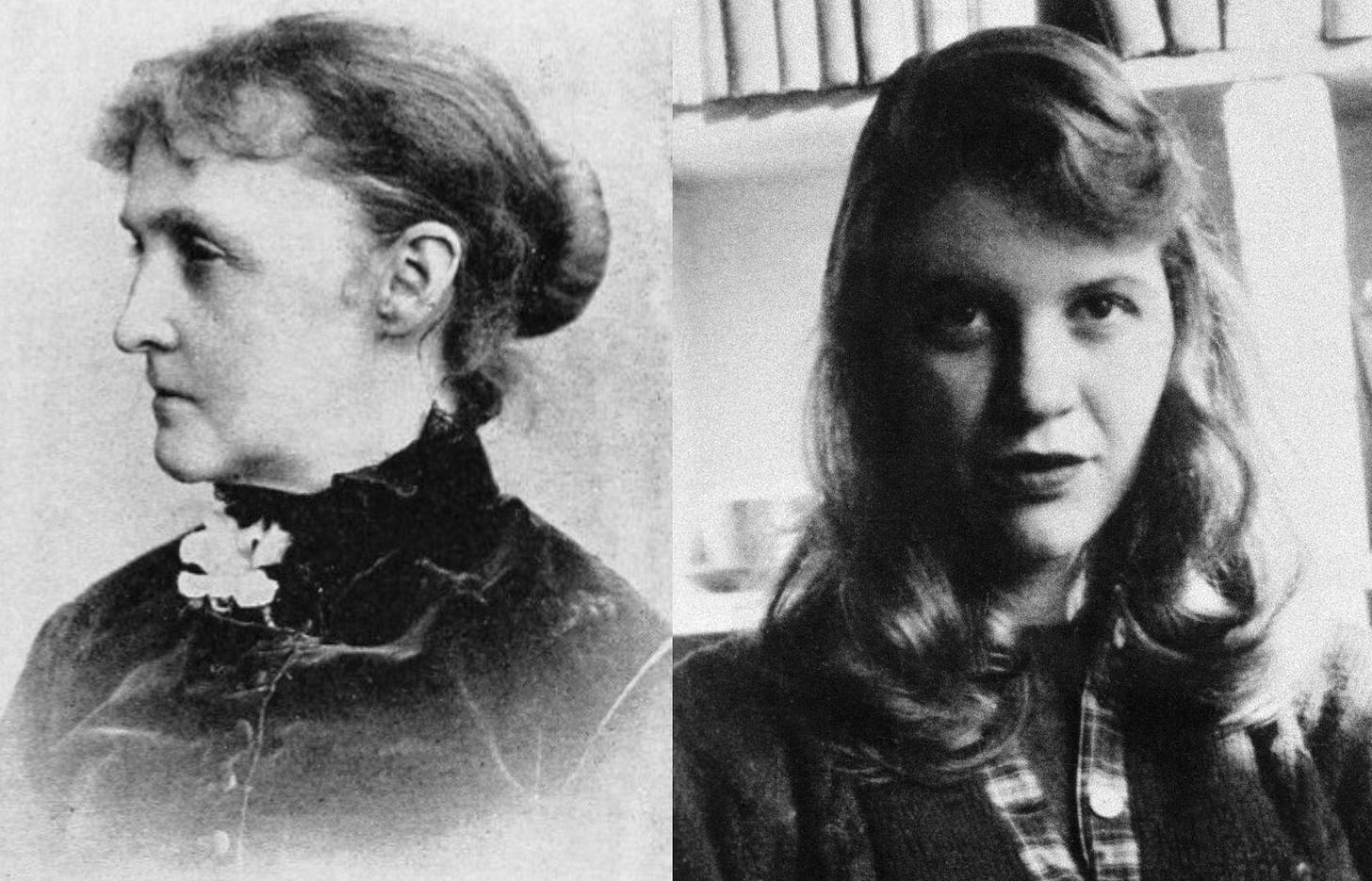

Piatt’s poem “The Shapes of a Soul” is one in which she most directly plays out the concepts of wildness and domesticity in relation to gender. The poem begins as what seems to be a conventional love poem, as we learn in the first and second stanzas that the speaker’s (male) beloved affectionately likes to characterize her soul as “a dove, a snowy dove” and as “a small flush’d flower.” The third stanza is where the poem turns from the man’s (or husband’s, we can assume) version of the female speaker’s soul, to her own understanding of herself:

Ah, pretty names for pretty moods; and you

Who love me, such sweet shapes as these can see;

But, take it from its sphere of bloom and dew,

And where will then your bird or blossom be?

In this passage we can see, in addition to the somewhat dismissive tone of the first line, how Piatt attributes the perception of these gentle, tame “shapes” for her soul to the physical space, the “sphere of bloom and dew,” where it resides. The word “sphere” here immediately conjures the concept of “a woman’s sphere” being in the home, the perfect context in which to view her as meek, beautiful, and mild—as the 19th century ideal of the “angel in the house.” What happens, Piatt asks, to this image of the dove or flower when it is removed from its approved environment?

In the latter half of the poem, Piatt answers her own question, noting that outside of this sphere, her soul would in fact reveal itself as wild, like “a tiger, fierce and bright” or even a snake (an animal that carries not only the metaphorical weight of wildness, but also sin, and sin’s biblical connection to women). However, the speaker of the poem also recognizes that even her attempt to uncover what she sees as the strength and power of her true nature is ultimately for naught, writing, “No matter, though, when these are of the Past,/ If as a lamb in the Good Shepherd’s care/ By the still waters it lie down at last.” The poem resolves with the image of the speaker’s soul made gentle and tame in the care of Christ in heaven, and, it seems, knowledge that the husband will revert to his own narrative of the speaker’s domesticity and softness after her death. However, the reader is also left with the unsettling recognition of how the husband’s and Christ’s expectations of the speaker are so closely aligned with one another (religion and marriage being in cahoots to domesticate women), while being antithetical to the speaker’s self-knowledge about her internal wilderness.

Have any of you heard of the poet Sylvia Plath? I’m going to guess that most of you have. In contrast to Piatt, Sylvia Plath’s work has enjoyed (as well as detested, probably) plentiful attention since she rose in the literary world in the 1960s as what poet and critic Honor Moore has identified as the “avatar of a new female literary consciousness,” and she has often been used as a symbol of the unhappy, repressed housewife in the era of The Feminine Mystique. With her biting self-awareness, tendency toward emotional extremity and dramatic monologue, and her ability to wrestle with moral and emotional complexity, we can imagine Plath would have appreciated Piatt as a poetic foremother had she had access to Piatt’s work.

Considered to be Plath’s masterpiece, the posthumous Ariel is filled with poems in the voice of a wife and mother living on the verge of crisis, in which her poetic perception and emotional instability bloom together with fierce, cutting, and gorgeous intensity. The psychological state of the speaker of these poems ranges between numbness and rage as she alternately succumbs to and fights against an overwhelming sense of confinement, as though her mind and heart are too big to fit inside the strictures of domestic life. For example, the poem “The Applicant” is constructed as a one-sided interview, where a collective “our” (who seems to be a representative of culture at large) queries an unnamed “applicant” who we learn has come looking for a wife. The sardonic humor and weirdness of the poem as the collective speaker asks,

Do you wear

A glass eye, false teeth or a crutch,

A brace or a hook,

Rubber breasts or a rubber crotch,

Stitches to show something’s missing?”

tips the poem immediately into the realm of nightmare or dystopian fantasy. But, as in all great dystopian writing, we also immediately recognize a distorted but true likeness of our own society where wounded, lacking men are considered to be entitled to accommodating, robot-like women who will take care of them, thus pointing to the horror of midcentury suburban middle class values.

Another theme that emerges in Ariel is the depiction of women as physicality powerful and wild but at risk from the repressive confines of patriarchal society. One such poem, “The Magi,” is inhabited by the speaker’s infant daughter whom she juxtaposes with the biblical magi. We might imagine a domestic, Christmas scene for the poem, where the house or flat has been decorated with images of the nativity. Throughout this piece, Plath builds a contrast between the abstraction of the magi who “hover like dull angels” with “ethereal blanks” as faces, and the fresh, rugged, and specific physicality of the baby girl who, at six months old, “is able/ to rock on all fours like a padded hammock.”

Rather than making the more expected comparison between the innocence of her infant daughter and the innocence of the infant Christ, Plath instead notices the irrelevance of these religious and philosophical narratives to her daughter, for whom “the heavy notion of Evil// Attending her cot is less than a belly ache,/ And Love the mother of milk, no theory.” In this way, Plath sets up “theory” and religion as an abstract, but also potentially repressive, hobby for the patriarchy, leading into the devastating rhetorical question that ends the poem –“What girl ever flourished in such company?” – inviting the recognition that the religious patriarchy is not a place for girls to thrive, but is, unfortunately, often inescapable. It’s also interesting to note the spatial juxtaposition here, as in contrast to the “hovering” of the patriarchal religious figures, which gaze over everything with dispassionate authority, the female infant’s “rocking” (which babies do for practice before they learn to crawl) denotes nascent potential, repetition, and repeated attempts – a bodily and preliminary motion.

I invite you, if you’re interested, to spend more time with the poetry of Piatt and Plath, both powerful women writers who brilliantly channeled their respective zeitgeists while also exposing their hypocrisies refusing to perform the acceptable version of the “poetess.” Despite her recovery by feminist literary scholars, Piatt’s work is unfortunately still a little tricky to find. Her page on the Poetry Foundation’s site doesn’t include any of the poems I discussed here (most of which are in this anthology), but has others to explore. The selection for Plath is predictably more robust.

In the third and final installment of this little series next month, I’ll focus on Chicana writer and feminist theorist Gloria Anzaldua and poet Gertrude Stein. I hope you’ll hang with me and join me there, and comment with any responses, observations, or questions you may have. What is your past relationship with these poets, if any, and how do they strike you now? Are there other poets or poems that you feel to be in conversation with these in their tensions between wildness and domesticity?

*This text of “The Funeral of a Doll” is from the The Concise Heath Anthology of American Literature, vol 2.

Thank you for resurrecting such brilliance. And thank you for reading poems to us - miss hearing your voice, love reading your voice. Brilliance finds lost brilliance - doing the good work, friend.