The Source of Poetry

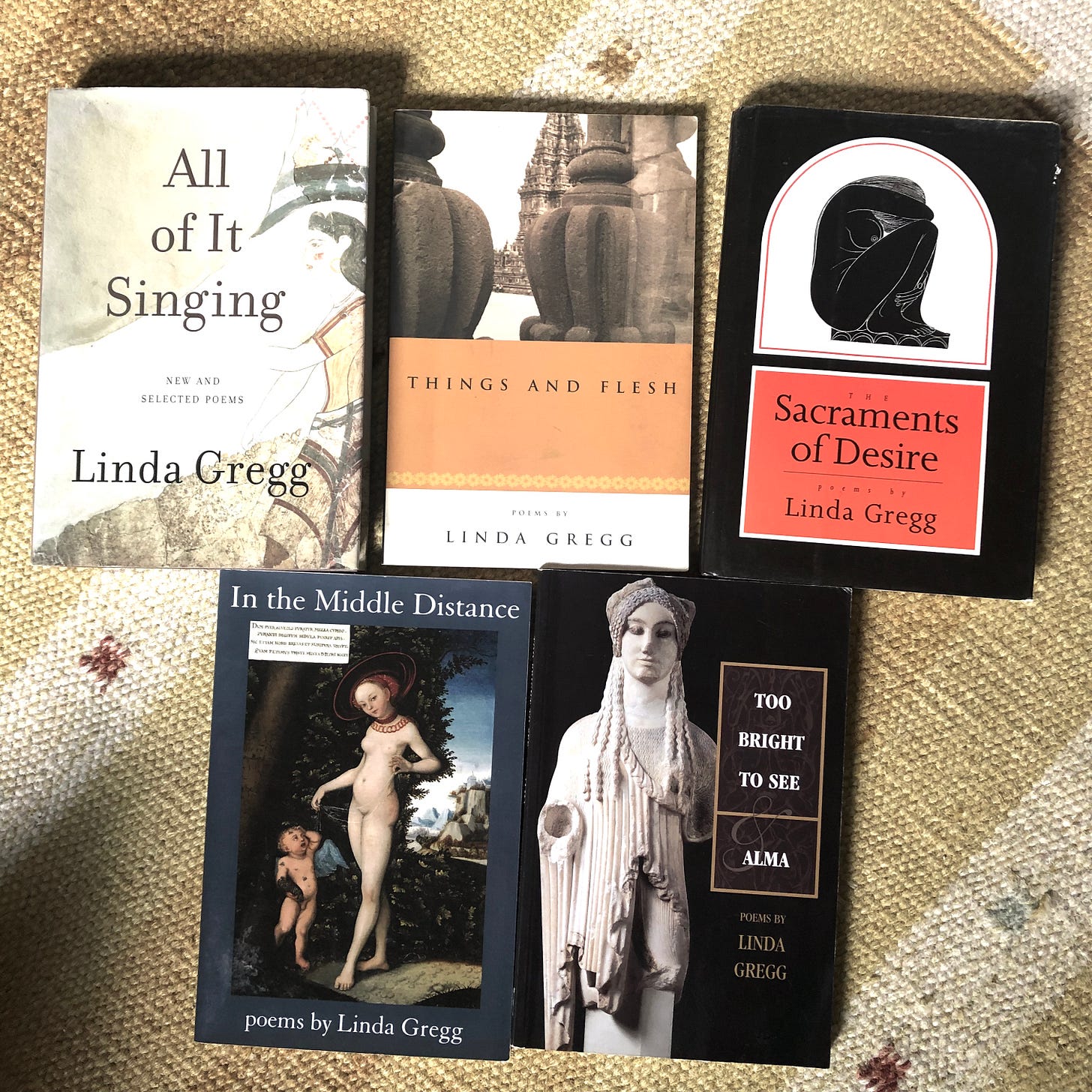

An Homage to Poet and Mentor Linda Gregg (Sept 9, 1942 – Mar 20, 2019)

On the first day of graduate poetry workshop with Linda Gregg in 2006, I was surprised when she began class by talking about her daily practice of walking around her neighborhood (NYC’s East Village), and then went around the room so that each of us—by way of introduction—could share what we did for exercise. Though I don’t remember her exact words, the point was about how we poets must remember our status as physical bodies in a physical world if we are to connect with that world, and ourselves, in our writing. While surprised by the conversation as an entrée to the semester (in my four years of undergraduate poetry workshops and one semester of graduate workshop never had a teacher mentioned physical activity as part of the writing process), the point struck me immediately as being right. I had come to college originally as a dance major, and had been practicing various styles of yoga since the age of thirteen. I felt, but had never articulated before that day, the connection between my compulsion to move and my compulsion to write.

The first assignment Gregg gave us that semester was, for a week, to write down six things we saw each day, trying our best to notice the “luminosity” in the everyday and, through the plainness and clarity of our language, retain it. In class the following week, we read our lists aloud and Gregg reacted to each item, sometimes with nothing more than a “Mmmmm…” or “keep going,” sometimes “No. This one is trying too hard” or “Yes, read that one again.” There seemed to be some sort of magic or divination at play: this was not the poetry workshop I was used to, and the rules were not only different, but also difficult to define. I had my doubts, as did some of my classmates. “How can she workshop what we see?” we wondered. But this wasn’t just a new way of writing or even seeing, it was a new way of being. Gregg’s weren’t assignments one could sit down and do at the last minute, or even in designated hours of the day; we learned that we had to see more often to see what mattered, and we couldn’t just watch our books, our screens, slot in our writing time like a class or coffee date. Being a poet was, we learned, a full time job. I’ve now used this exercise in many of my own workshops that I’ve taught over the years, and though I try to make the method and goals more transparent than Gregg did, I find it to be a wonderfully useful practice for poets and artists of all kinds, as it invites us all to be more present in our own lives.

“It Goes Away” from In the Middle Distance (2006)

Linda Gregg’s feedback methodology was almost entirely focused on global issues of impulse and resonance rather than on surface-level craft issues or line edits. Her operating assumption was that if we had written a poem, it was important to us, and therefore important that the poem be a full and deep expression of that importance, of the “source” of the poem’s making. She was more likely to praise a poem for its emotional depth and sincerity (or critique it for a lack of these) than to focus on elements like syntax or a misplaced line break. By the same token, however, the precision of the poem’s images and communication of some emotional or intellectual gesture were always integral to Gregg’s understanding of the poem’s project, so she would question the appropriateness and truthfulness of an image, a description, a setting, if it felt at all artificial or forced. Gregg is not who I’d go to for formal concerns regarding meter, syntax, or lineation (though she has a fine grasp of all of these), but I have returned to her work again and again over the years to remember why I write poems in the first place. One of her mantras, which she got from Jack Gilbert and which I’ve repeated to myself many times was: “Don’t lose the poem.” Another: “Don’t be clever” (or “No tap-dancing”).

Gregg’s approach to teaching poetry workshop included an automatic and profound respect for every student present due to an assumed commonality of purpose: everyone in the room is there because they love poetry and are dedicating their lives to it. Therefore, the group is linked by a shared devotion and a common desire to grow as artists, to be challenged, to give themselves over to the student/teacher apprenticeship. This classroom atmosphere stood in stark contrast to the more familiar model of workshop that assumes a shared ambition toward publication and professionalization rather than a shared love of poetry’s beauty, mystery, and power. A common side effect of the latter model is also the assumption of a competitive (and somewhat Oedipal) atmosphere in which some young writers will “hack it” and others will not. The teacher is in the position, then, of defending his/her own status against the young, cocky newcomers, and the newcomers vie for position to find approval from and eventually replace their teacher.

The description I’ve offered here may be a somewhat extreme characterization, but it isn’t far off from the psychological reality of many writing workshops I was a student in (and I’ve been in many). A valid counterargument to my distinction here is that Gregg’s approach could be naïve: not every student in a workshop has actually dedicated their lives to poetry, and it’s a safe assumption that most (if not all) students in graduate-level workshops do have the expectation of publication and professionalization to some extent, at least. Isn’t it useful (and even necessary) for students to receive candid information about publication and the realities of “po-biz”? Yes, probably so. But putting some of writers’ seemingly bottomless professional anxiety aside might also free up new possibilities in workshop, allowing young writers to become more deeply engaged with concerns of poetry and art-making, and allowing them to focus on process, source material, and social purpose.

Another critique of Linda Gregg’s pedagogy that I heard was that her aesthetic was so firmly rooted in earnestness and plainness that she wasn’t always receptive or attuned to styles and aesthetics that come from a different set of values, particularly contemporary styles that value irony, obfuscation, or cleverness. That is true. Ultimately, though, I felt that being challenged to say something in our poems, to defend and communicate our ideas (rather than just our aesthetic choices) improved the poems of everyone in that class no matter their style. Gregg wasn’t impressed by a savvy, artful poem if she felt there was no “there there,” or that the poem was using style as a form of defense, but she also wasn’t ignorant of experimental forms or the important contributions of Modernism and its descendants. I remember one class in which a student was somewhat stridently defending his poem in which he’d used unconventional capitalization and punctuation for no apparent reason. He was arguing with Gregg based on an assumption that she didn’t like “experimental” work or know what young people were writing these days, and her response was something like “if you think this is experimental, you’re about 100 years too late.”

While I’ve had many accomplished and influential poetry mentors for whom I’m grateful, Linda Gregg is the mentor’s voice I still find most often in my head when I’m writing, and by whom I’ve been most inspired in my own teaching. More than any other mentor, she guided me not just in the craft of poetry but also in the life of poetry, giving me a way to integrate my early education that nurtured my love of language and the natural world with my adult life as an artist.

Our friendship is now nearly two decades old. And although–since her death from cancer in 2019–I can no longer enjoy the long (sometimes exhaustingly long) phone conversations filled with talk of poetry, gossip, her smoky laugh, anecdotes from her lifelong devotions to Jack Gilbert, the Greek island of Paros, and thrift store finds, or spend long, whiskey-blurred afternoons in her apartment or walking around the East Village, our friendship is ongoing. I converse with her, still, when I read her poetry, hear her words in my head, or feel her energies coming through me when I teach my own poetry students. Though I developed a clearer perspective on her flaws and graces than I had at the age of twenty-four when I first stepped into her class at the University of North Carolina Greensboro, her voice in my writing and teaching life continues to be profound.

For example, I’ll always remember a phone conversation I had with her in 2016 when I was a doctoral student at the University of Cincinnati. Linda reprimanded me for choosing not to submit a poem for a one-off workshop with poet Carl Phillips. When I explained to her that I was already getting a lot of feedback on my work these days, and anyway I didn’t have anything new to submit and didn’t want Phillips to tear up a more “finished” poem, she told me this story: “Last night I was talking to Louise [her twin sister] on the phone and she was saying to me, ‘Linda, whenever I was in a new place I would look for someone that made me feel comfortable, a friend like myself to spend time with. But you, Linda, all through your life you always sought out the greatest poets to learn from.’ And she’s right,” Linda went on, “I never went out looking for approval, I always put myself in the way of something significant.”

The last time I spoke with her was about two weeks before she passed away in March 2019. I knew she was ill, though not how ill at that point. I used to take notes during our phone conversations, so I’m glad that I wrote down what she said to me that day. As our conversation came to a close, Linda said, “I’ll leave you with this. Despite everything that’s happened and despite all the pain, I’m happy every day. I just really love living, and want to do it as long as I can. I guess I was just born happy.”

Are you familiar with Linda Gregg’s poetry? Who have been your most significant mentors and what from them do you carry with you?

Note: Pieces of this remembrance were previously published by AWP Writer in 2016, three years before Gregg’s passing.

Beautiful! I've loved Linda Gregg's poems for a long time and it is wonderful to read about who she was as a teacher and friend--it's inspired me as both writer and teacher today. Thank you!