(Re)learning the Future

A road trip, an identity crisis, a glimmer of golden thread in the grass

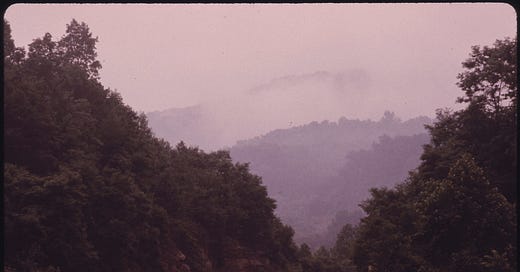

We were winding our way down through the mountains of West Virginia on highway 64, our usual route between Cincinnati, Ohio—the city we’d left in the first weeks of the pandemic in 2020—and Durham, North Carolina—my hometown that we’d moved or, should I say, fled to, to be close to family when the world so suddenly recalibrated itself. Now it was April 2022, and we were returning from a weeklong trip to visit Cincinnati friends, and for Brandon to have some in-person meetings at the company for which he works remotely.

Since we’d moved, I was feeling more connected to family and community, but creatively and professionally at sea. Having spent basically my whole adult life in academia or other art institutions, following poetry fellowships, teaching jobs, and graduate programs around the country and working toward the dream of a tenure-track university position, in the end I’d turned down the elusive tenure-track job, the first (and probably last) one I’d ever been offered, in those early weeks of lockdown. The invitation from a liberal arts college in Maryland had come in just seven days after we’d gone under contract on our new house in Durham, so, although declining the position felt like a tearing away of something deep inside me—a something I later recognized as my professional identity—the choice had already been made. Since then, I’d been working to deprogram myself from the worldview I’d adopted over all those years—the one that told me that I needed an institution to legitimize not only my work, but me as a person. What could I do now that I’d left the one path I’d ever followed? The signs on this new trail, the one that forked off to the left when coronavirus altered all our courses, the one pointing toward something called “home,” were difficult to read, being written in symbols simultaneously strange and familiar.

I had been teaching online poetry workshops and freelancing as an editor and copywriter while also looking for my place in local climate activism. I volunteered my time for a couple of organizations but was missing the camaraderie and sense of belonging I’d had in university English departments, as well as in the activist group I was part of in Cincinnati. Should I look for jobs in high school teaching? Go back to adjuncting? Try to work for a climate nonprofit? Look for some university staff role? Having always trusted the promise of The Plan, I’d never made a plan B. Thus, my progress on this new path was slow and disjointed, like a bird pecking in the grass. I could find little bits of meaning—seeds and twigs—but where was the golden thread I could follow, the one that would show me how and where to build my nest?

So, on that spring day as our car drove down the highway set deep in the mountain’s gashed side, I spoke aloud some questions from the constellation that hovered over the passenger side of the car and Brandon held them with me, lightly. What was my new path, and how would I find it? Floating together with these questions: the wisdom, words, and actions of writers I was reading and people I admire—Adrienne Marie Brown, Robin Wall Kimmerer, Bayo Akomolafe, Greta Thunberg, Martin Shaw, Robert MacFarlane, Richard Powers, and an activist and fashion designer named Arielle whom I’d met through Citizens Climate Lobby and who had recently left her life in New York to build an off-grid homestead in West Texas. In an Instagram post that week, she’d written, “I am no longer fighting old systems, but am instead putting all that energy into creating new ones, from the ground up.” I told Brandon about her words that had struck me so deeply, and wondered aloud what my version of that would look like, since I would surely not be living off grid in Texas.

The terrain was changing now, the rocky land opening up into a wide valley below us as we crossed the state line into Virginia. A spectacular view. Oliver was asleep in the backseat, so whole minutes could pass with only the sound of the engine and the tires’ contact with the road. “I’m going to start a school,” I said. The words surprised me when I heard them. “A place for people to learn who we need to be in the future, so we can start now.” “Yes,” Brandon said, because we both knew it was true. Within five minutes, he’d helped me name The School for Living Futures, and within the name was the essence of the thing, like the title of a poem I wanted to write. I could see it now: the end of the shining thread I held between my fingers.

I’ve been reflecting on this story the past couple of weeks. Naturally, as SfLF closes out its first year of programming, I’ve been thinking about its conception story. But it’s also reverberated as I’ve recently been immersing myself in the work of

, who talks about “turning aside from the one big path that was meant to lead to the future” and “asking what else is worth doing with the time we have.” His recent book, At Work in the Ruins, which is making its way to the top of the stack on my nightstand, promises to address what tasks are “worth giving our lives to, given all we know or have good grounds to fear about the trouble the world is in.”I have a pretty good idea of what Hine will say this work is (having watched an hourlong recording of a book talk as well as reading his newsletter and listening to his podcast), and I’ll share more about his ideas when I’ve read the book. But this image of leaving the “one big path” is one with which I suspect many of us can connect, whether through professional, personal, or even spiritual detours. Of course, Hine isn’t talking about (or only about) diversions in our individual stories, but rather a collective, cultural rerouting. The “one big path” is the grand narrative of progress, the notion that life as we know it goes on forever, and that science and technology will solve the world’s ills. That path has, by this point, been proven false by our decades-long failure to take meaningful action to curb carbon emissions, such that—even knowing all we know—enormous losses are here, and even greater losses loom.

And yet (and yet!) there is still work to be done.

That is the story I invite you to hold with me at the changing of another year. The story of the person (you?) who, realizing there was no longer a choice—for the choice had already been made in millions of increments by our ancestors—left the wide, straight path for a new direction, the plan B you’d never planned. Now imagine that billions of people are doing this at the same time as you are. Picking up the golden threads they find lying at their feet and following them toward a place they recognize, though they’ve never been there before.

Thank you for following me here. I thought I would begin this School for Living Futures series of posts by answering the question I’m often asked about how SfLF came to be. My vision for this section of Bright Shards going forward is as a place to share our story as we change and grow, and to highlight the some of the amazing climate-engaged work from artists, scientists, activists, writers, and wise people through interviews and features.

I send you all blessings during this season, and will meet you again after the turning of the year.