Apricot Trees Exist

magical thinking, the magic of being, and Inger Christensen’s Alphabet

Merry and tragical? Tedious and brief?

That is, hot ice and wondrous strange snow.

How shall we find the concord of this discord?-Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act 5, Scene 1

In his introduction to The Modern Library edition of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream – a play that, more than any other of Shakespeare’s works, explores liminality and the blurring of opposites – Jonathan Bate refers to the playwright as “the poet of double vision”: “The father of twins, he was a mingler of comedy and tragedy, low life and high, prose and verse.” Bate goes on to suggest that the “second form of sight” that guides the bard’s invention is “magical thinking,” a mode of being that “finds correspondences between earthly things and the divine,” a way of creating sense from the seemingly random and even incoherent workings of fate. Significantly, this joining of opposites is not merely thematic (as we see in its blurring of waking and sleeping, day and night, animal and human, mortal and fairy, etc.) but also formal: A Midsummer Night’s Dream combines prose (20%) and poetry (80%) as well as embedded songs, comic poetry, and a play within the play, thus enacting the resolution of contradictions we find in the story’s happy ending.

In these first days of 2024, I’ve been pondering magical thinking in art, a concept in which I first became interested a few years ago while studying hybrid poetic forms (works that combine poetry with other forms/mediums) as part of my doctoral dissertation. While reading hybrid poetries from across time and place–from Dante and Shakespeare to Gloria Anzaldua, Anne Carson, and Claudia Rankine–it occurred to me that these writers, through formal means, had all concocted a similar spell: The magic of reconciling irreconcilable truths, of holding both beauty and devastation in the same hand. Incidentally, I defended that dissertation in February 2020, less than a month before known reality abruptly changed, millions went into lockdown, and magical thinking became a means of psychological survival and, at times, distress, for so many of us. What “facts” were we to believe? And how would we reconcile the advice of scientists and other officials with the necessities of our individual lives? In this new, nonsensical world where the bodies of our loved ones were called a threat and staying home alone in front of a screen was virtuous, what words and actions might save us?

In Shakespeare’s Elizabethan England, when the study and understanding of scientific systems we now take for granted did not yet exist or were only beginning to emerge, magical thinking, superstition, and dream could account for the seemingly random events of disease, draught, romantic infatuation, or beauty. But even now in our current, science-saturated iteration of modernity, we are constantly confronted with contradictory “facts,” whims of fate, and realities too large and too devastating–war, oppression, personal loss, and the unfolding climate disaster–to integrate without some form of (or should I say, formal) magic. Which is where art comes in. Charles Baudelaire seems conscious of this fact when, in the introduction to his landmark collection of prose poems, Paris Spleen, he overtly links his formal innovation with the book’s magical, or supernatural qualities. Addressing his editor, Arsène Houssaye, the poet writes:

I send you here a little work of which no one could say that it has neither head nor tail, because, on the contrary, everything in it is both head and tail, alternately and reciprocally…. Take away one vertebra and the two ends of this tortuous fantasy come together again without pain. Chop it into numerous pieces and you will see that each one can get along alone. (ix)

With its innovative melding of poetry and prose, Baudelaire depicts his book as a magical beast, a creature that is not bound by the conventional laws of life and death, opposites, or categories. His utilizing (and, in effect, inventing) a hybrid poetic form has made what should be impossible now possible.

All of this brings me to the book Alphabet by Danish poet Inger Christensen, first published in Denmark in 1981 and translated into English by Susanna Nied for publication in 1982. It’s one of my favorite poetry books of all time – so much so that my only tattoo is inspired by its first line. I was compelled to pick it up to reread on New Year's Day this year because in these times, every new year promises to be more irreconcilable than the last and, simply, I was needing some magic.

Alphabet is a litany, an abecedarian (each section representing a letter of the alphabet by using heavy alliteration), and also mathematically constructed to follow the Fibonacci sequence, where the number of lines in each section is the previous two added together. Here is the text of the first four sections, and audio of the first eight:

1 apricot trees exist, apricot trees exist 2 bracken exists; and blackberries, blackberries bromine exists; and hydrogen, hydrogen 3 cicadas exist; chicory, chromium citrus trees; cicadas exist; cicadas, cedars, cypresses, the cerebellum 4 doves exist, dreamers, and dolls; killers exist, and doves, and doves; haze, dioxin, and days; days exist, days and death; and poems exist; poems, days, death

With its invocational quality, the poem begins almost like a version of Genesis I, calling the earth into being through language. In section 10 (J in the abecedarian), however, the reader learns that “atom bombs exist// Hiroshima, Nagasaki…” after which nothing on earth, and therefore the poem, can be the same. So, in the following section, the world has become imminently and unavoidably mortal, and creation begins to operate in reverse: “people, livestock, dogs exist, are vanishing;/ tomatoes, olives vanishing, the brownish/ women who harvest them, withering, vanishing,/ while the ground is dusty with sickness…” (26). As you can imagine, the Fibonacci pattern means that the sections get quite long by the time we get to the letter N, where the book leaves off mid-alphabet for nuclear destruction. What began as the enumeration of life’s splendor ends as an elegy mourning the profound, irretrievable losses humanity has perpetrated on the planet. By this point in the poem, the earth has transformed into a post-nuclear wasteland wherein the cities are poison and children are living in caves.

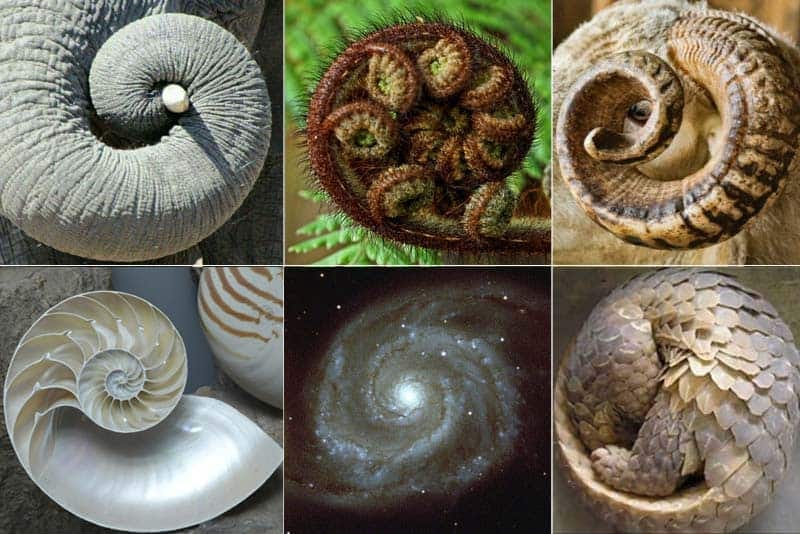

Christensen’s exquisite use of language does not claim to heal or “solve” the sickness and death wrought by modernity and its death-drive, nor does it undermine the gravity of the destruction. Rather, the hybridity and, thus, the magical thinking of the poem comes from its collaboration with both human-made (alphabetical) and organic (mathematical) orders as a method of structuring some understanding of ecological disaster, of the end of the world we know and love. In other words, to comprehend the terror of mass extinction, Christensen concocts a spell from an essential pattern within creation, the design we find in the structure of leaves, trees, seashells, ferns, spider webs, and even the shape of an ocean wave. Death inseparable from life, as always.

“Hope” is a buzzword in conversations about the climate crisis. Is there hope or isn’t there? people want to know. But there’s no simple answer to that question, where the affirmative becomes an excuse for complacency, and the negative an excuse for nihilism. And it’s the kind of question science cannot answer. Alphabet is not a hopeful poem, but it’s a poem that gives me hope. It is a “dancing in the cracks” of modernity, as philosopher and writer Bayo Akomolafe would say, and an example of how art can offer other ways—besides (or alongside) science—of knowing the “truth” of the plight we’ve created. A knowing electrified by intimacy, connection, and feeling. As

writes in his recent book, At Work in the Ruins, the job of the artist is not to “deliver the message” of climate change or any other scientific or political reality, but to “do justice to the strangeness and the messiness of life.” For me, Christensen’s poem sits high among the pantheon of books that do justice to the strangeness of this time in which we’re watching the old ways (literally) burn, but cannot yet see what will be born from the ashes.I’m holding such poetry close these days, as it’s the best and only way I’ve found concord in this discord. That is, hot ice, and wondrous strange snow.